This is a well-documented perception gap.

http://www.pbs.org/speak/speech/prejudice/women/

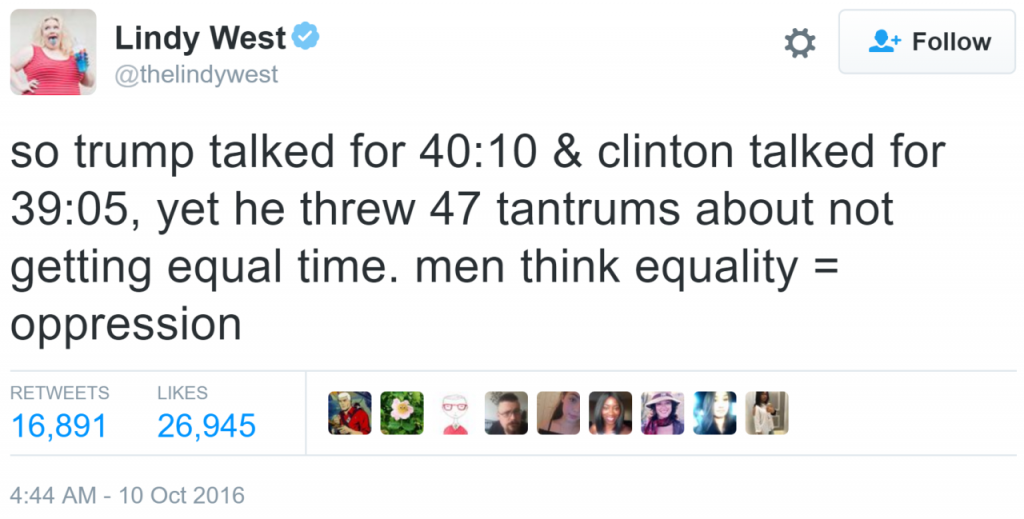

In other public contexts, too, such as seminars and debates, when women and men are deliberately given an equal amount of the highly valued talking time, there is often a perception that they are getting more than their fair share. Dale Spender explains this as follows:

The talkativeness of women has been gauged in comparison not with men but with silence. Women have not been judged on the grounds of whether they talk more than men, but of whether they talk more than silent women.

In other words, if women talk at all, this may be perceived as ‘too much’ by men who expect them to provide a silent, decorative background in many social contexts. This may sound outrageous, but think about how you react when precocious children dominate the talk at an adult party. As women begin to make inroads into formerly ‘male’ domains such as business and professional contexts, we should not be surprised to find that their contributions are not always perceived positively or even accurately.

http://inthesetimes.com/article/16157/our_feminized_society

“If there’s 17 percent women, the men in the group think it’s 50-50,” she told NPR. “And if there’s 33 percent women, the men perceive that as there being more women in the room than men.”

The idea of a gender perception gap is borne out by studies in other areas. In one study on gender parity in the workforce, sent my way by colleague Flavia Dzodan, it was found that men “consistently perceive more gender parity” in their workplaces than women do. For example, when asked whether their workplaces recruited the same number of men and women, 72 percent of male managers answered “yes.” Only 42 percent of female managers agreed. And, while there’s a persistent stereotype that women are the more talkative gender, women actually tend to talk less than men in classroom discussions, professional contexts and even romantic relationships; one study found that a mixed-gender group needed to be between 60 and 80 percent female before women and men occupied equal time in the conversation. However, the stereotype would seem to have its roots in that same perception gap: “[In] seminars and debates, when women and men are deliberately given an equal amount of the highly valued talking time, there is often a perception that [women] are getting more than their fair share.”

How do you give men the impression of a female majority? Show them a female minority, and let that minority do some talking. This is how 15 minutes of Fey and Poehler becomes three hours of non-stop “estrogen,” how a Congress that’s less than 19 percent female becomes a “feminized” and male-intolerant political environment, and how one viable female Presidential candidate becomes an unstoppable, man-squashing Godzilla. Men tend to perceive equality when women are vastly outnumbered and underrepresented; it follows that, as we approach actual parity, men (and Elisabeth Hasselbeck, for some reason) will increasingly believe that we are entering an era of female domination.